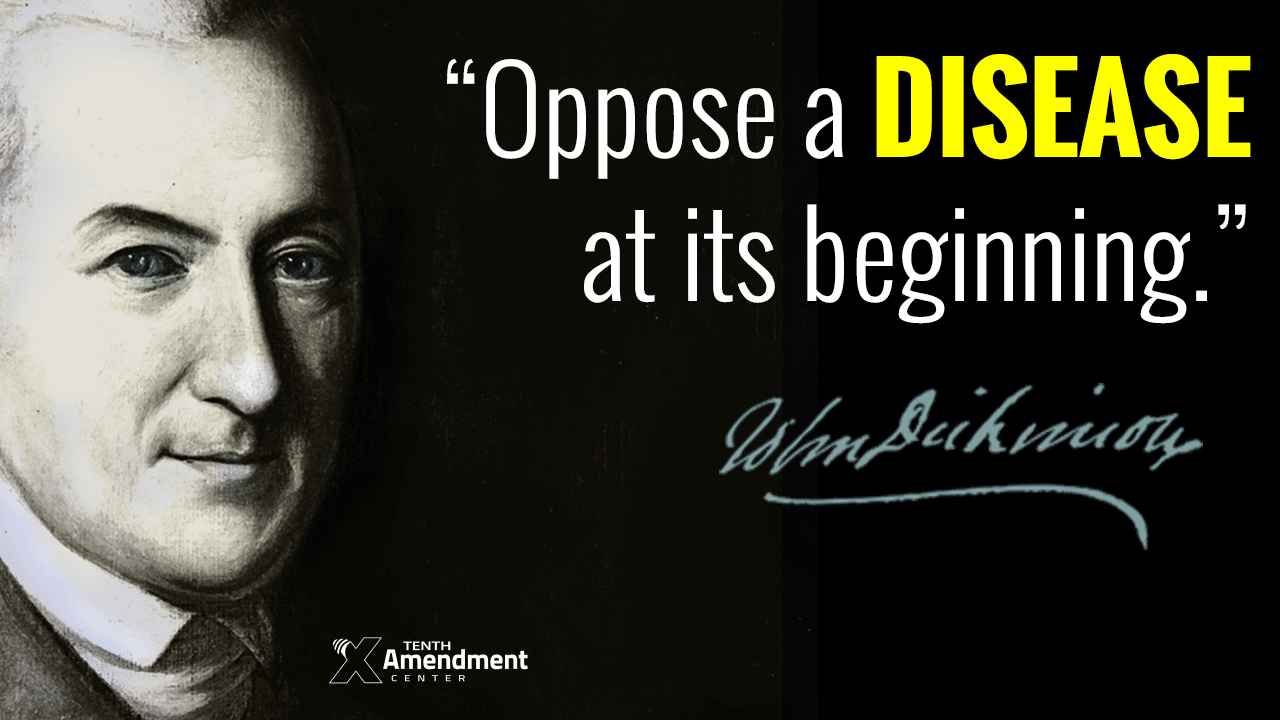

Tenth Amendment Center: Oppose a Disease at its Beginning

If you give politicians an inch, they’ll take a mile.

John Dickinson was one of the leading writers in the early days of the conflict. He insisted that the colonists needed to “oppose a disease at its beginning,” before the sickness could spread.

Writing under the penname “A Farmer in Pennsylvania,” Dickinson published a series of essays now known as Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania in a Philadelphia newspaper. Dickinson used his pen to vigorously oppose the Declaratory and Townshend Acts.

The American colonist had effectively nullified the hated Stamp Act by refusing to enforce it and actively resisting its implementation. They defeated the mighty British empire utilizing virtually every strategy and direction available – from resolutions and declarations, to protest, resistance and even non-compliance by government officials. But the British weren’t about to concede their authority over the colonies. When Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, it passed the Declaratory Act declaring its absolute political superiority over the colonies. This Declaratory Act asserted that Parliament could make any laws binding the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

A year later, Parliament put its words into action with the passage of the Townshend Acts. These laws imposed new taxes on the importation of paper, paint, lead, glass, and tea, and expanded the British government’s power to fight smuggling. The Townshend Acts included the New York Restraining Act. suspending the Assembly of New York’s legislative powers as punishment for failing to fully comply with orders from the crown.

Dickinson warned that failure to confront this assertion of British power then and there would lead to dire consequences and loss of liberty down the road. In the sixth Letter from a Farmer, he argued that letting the government take on even a little bit of new power would eventually lead to bigger and bigger usurpations in the future.

“All artful rulers, who strive to extend their power beyond its just limits, endeavor to give to their attempts as much semblance of legality as possible. Those who succeed them may venture to go a little further; for each new encroachment will be strengthened by a former. ‘That which is now supported by examples, growing old, will become an example itself,’ and thus support fresh usurpations.”

He continued with this theme in the ninth essay, chronicling the ways that the British Parliament, the Crown, and English judges were expanding their authority over the colonies. He concluded the essay with a warning in the form of a Spanish history lesson.

Spain, Dickinson said, was once free. Its governance was similar to that of the colonies. No money could be raised without the people’s’ consent. But an ongoing war against the Moores required funding. The king received a grant of money to fund the fight, but he was concerned it might not be a sufficient amount to pay for the war effort long-term. So, the king asked that “he might be allowed, for that emergency only, to raise more money without assembling the Cortes.” The Cortes was the Spanish representative body — similar to the Parliament.

Dickinson noted that the proposal was “violently opposed by the best and wisest men in the assembly.” But the majority approved the measure. And thus began a slide down a slippery slope. As Dickinson described it “this single concession was a PRECEDENT for other concessions of the like kind, until at last the crown obtained a general power of raising money, in cases of necessity.”

The legislature gave an inch and the king took a mile.

Dickinson wrote:

“From that period the Cortes ceased to be useful—the people ceased to be free.”

He closed the letter with these Latin words of instruction:

Venienti occurrite morbo.

Oppose a disease at its beginning.

John Adams made a similar argument also using a Latin phrase: “Obsta principiis.” which means withstand beginnings, or resist the first approaches or encroachments. Colloquially, we would say, “nip it in the bud,” which is exactly the phraseology Adams used.

“Nip the shoots of arbitrary power in the bud, is the only maxim which can ever preserve the liberties of any people.”

Adams and Dickinson both recognized an important truth. When you allow a government to chip away at the limits on its power, eventually the dam will burst. You will end up with a government exercising virtually unlimited authority – arbitrary power. At that point, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to rein it back in. Adams wrote:

“When the people give way, their deceivers, betrayers, and destroyers press upon them so fast, that there is no resisting afterwards.”

You can’t tear down a fence and then expect the animals to stay in the field. Once the fence is gone, the animals will wander. The same thing happens when we tear down fences around government power. The government will wander further and further away from its restraints and accumulate more and more power for itself. As Dickinson wrote, “Each new encroachment will be strengthened by a former.”

Politicians love to use emergencies as an excuse to expand their own power. But once the new policy is in place, it never goes away – even after the emergency has long passed. In fact, the new policy almost always becomes a springboard to expand government power even more. The Patriot Act is a perfect example. Nearly two decades after 9/11 the federal government is still using that act to justify spying on all of us all the time.

This is why we must hold the line on the Constitution: Every issue, every time. No exceptions, no excuses.

Mike Maharrey

November 27, 2019 at 03:44PM